The building we are in today is the Groothandelsgebouw; the Wholesalebuilding, opened 65 years ago in 1953, where wholesale companies would sell their products such as ironware, perfumes and shampoos, curtains and furniture and what not to retailers and craftsmen all over the city. It was a gigantic beehive in which hairdressers, carpenters and plumbers drove in with trucks, cars, bicycles or hand carts, taking the viaduct at the back or the elevated roads in the front to exit fully loaded with products and devices needed to run their businesses and shops.

It is a fascinating building in its design and program and quite unique. Maybe you have noticed its curious not-quite modernist design or were startled by this peculiar boxy volume on the roof containing a cinema. But this famous cinema Kriterion is much more than a folly on top of a building or the gadget of a screen which turns into a window. It has another significance that I want to shortly focus on: How Kriterion was at the same time the symbol of the resurrection of Rotterdam as well as a tool (a propaganda tool) in constructing its post war image by the powers that be. It is no exaggeration to state that this newly created image was so powerful that its influence lasts to this very day.

When the Wholesalebuilding was opened in 1953, the Queen pushed a button which activated a relic on top of the roof: the horn of the Statendam, the flagship of the Dutch merchant navy that had tragically been burned and sunk during the city’s bombardment. The Groothandelsgebouw was the symbol and first manifestation of the resurrection of the city. The size and scale of the building were unprecendented, bigger than ever before.

The particular combination between program and location says a lot: right next to the central station we find a palace for wholesale, not for culture, commerce or nightlife, but for business. The entrée of the city says: This is a city of business, not so much of the workers, as Rotterdam is usually seen and described, but of business men and entrepreneurs.

The Groothandelsgebouw is deeply rooted in that world: during the hunger winter of 1944 the business men, the Chamber of Commerce and the managerial elite of the city dreamt up big plans for when the day of liberation would arrive. Throughout the war this elite, based on the captains of industry of Rotterdam had gained influence, developed visions, created common ground and took over. The tearoom on the modernist Van Nellefabriek was the place where all this was plotted, symbolically distanced above but with a view of the city.

The destruction by the bombardment was a traumatic experience that for reasons of psychological healing as well as social stability had to be forgotten and surpassed: “we are not looking at her tragedy, we are looking at her glory”.

This is where the new myth of Rotterdam started, the city that before the war was known as the ugliest worker city of the NL, inert, hard to change, with no appetite for beauty nor innovation. The destruction created the need and the opportunity for a new narrative: the city which rises like a phoenix from the ashes. A this point the urban identity was constructed of a city with rolled up sleeves, always building and constructing, never looking back, unsentimental, entrepreneurial and working hard.

The city organized an avalanche of manifestations, reconstruction tours, magazines and other propaganda, uniting the population in one collective effort to surpass the past.

This was the new cultural hegemony enforced by the elite of captains of industry and harbor barons in close alliance with the modern architects like Maaskant, who was right in the middle of it, designing the Hilton hotel, the Lijnbaanflats, the Hofplein schools and so many other buildings surrounding us. Never has there been such a fruitful cooperation between city, architecture, housing corporations and business parties, working steadily on the Makeable city until the demise of the welfare state in the eighties.

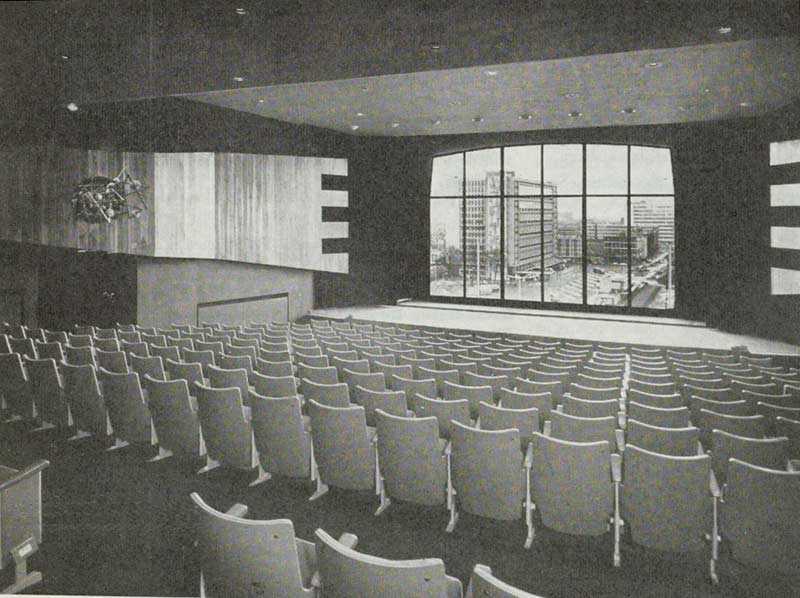

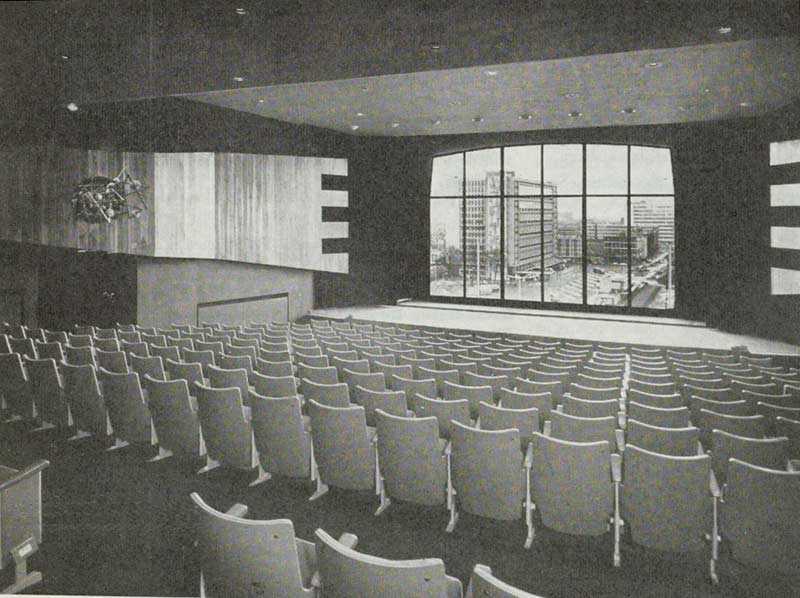

The design of Kriterion epitomizes all the ambitions of the new leaders. Like the tearoom it hovers above the city, distanced but with a view. Kriterion is designed to showcase the continuous construction outside with the dramatic gesture of opening the curtains, the big window giving a majestic view of the new business center of the biggest harbor in the world. After 90 minutes of Hollywood entertainment it showed the residents of Rotterdam the remarkable accomplishments of their city, immersing them in the spectacle of reality outside. It evokes pride, yes, but also has an element of intimidation by humbling the spectator and making them an accomplice in this collective building frenzy.

It seems like a miracle that even after the collapse of the makeability ideals the powerful myth of Rotterdam as a city forever in the making is still very much alive. It has been created and enforced, but now it feels natural and dear. The city still uses the retorics of the reconstruction era: Hoor hier bonkt het nieuwe hart van Rotterdam: Hear the pounding heart of the new Rotterdam. It is a campaign that uses a new lingo but still aims to do the same old thing: fire up the spirit of collective support for the ongoing urban policies.

And it’s not only the city but also the grassroots and new generations have adopted the myth like the magazine Vers beton / Fresh Concrete, combining critical journalism with the smell of Rotterdams first and foremost building material.

That is what propaganda can do, that is what architects like Maaskant can design, this is where we are right now.