Looking at the cities that were built from scratch during the fifties and sixties all over the world, it is astonishing to see how the world population growth was accommodated along very similar lines in places very remote and different in culture and political background. Whether one looks at the Villes Nouvelles around Paris, the New Towns close to London, the new parts of Stockholm or cities like Hoogvliet in the Netherlands, a similar strategy and design method was applied. These cities were erected based on the ideas of the garden city, and a hierarchical ordering and zoning of functions relying on modernist urban planning. Starting in the London region in the forties, these New Towns soon became the panacea for urban growth in Western Europe. Harder to understand is how the same modernist urban planning started to pop up and spread in developing, decolonising countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. The export of these New Town principles can only be understood from the background of the Cold War period, in which the east and west were both competing for the loyalty of the third world in every which way they knew how. While the endeavours of the Soviet Union in this field remain largely unresearched, it is clear that the US sent out a number of urban planners and architects to countries in strategic places like the Middle East. The hypothesis soon formed that urban planning was considered to be a powerful instrument in cold war politics, and that the export of architecture and planning functioned as a means of cultural in stead of political colonization.

A vivid illustration of this hypothesis is formed by the fascinating coalition of two parties, the Greek planner Constantinos Doxiadis and the American Ford Foundation, who together formed a powerful duo of vision and money. They had an intense relationship with longlasting consequences for developing countries in the Middle East and Africa. Their cooperation shows how the socalled neutral introduction of large scale development urban planning was anything but neutral. In fact it was heavy with promises of freedom, democracy, and prosperity and laden with ideals of community and emancipation.

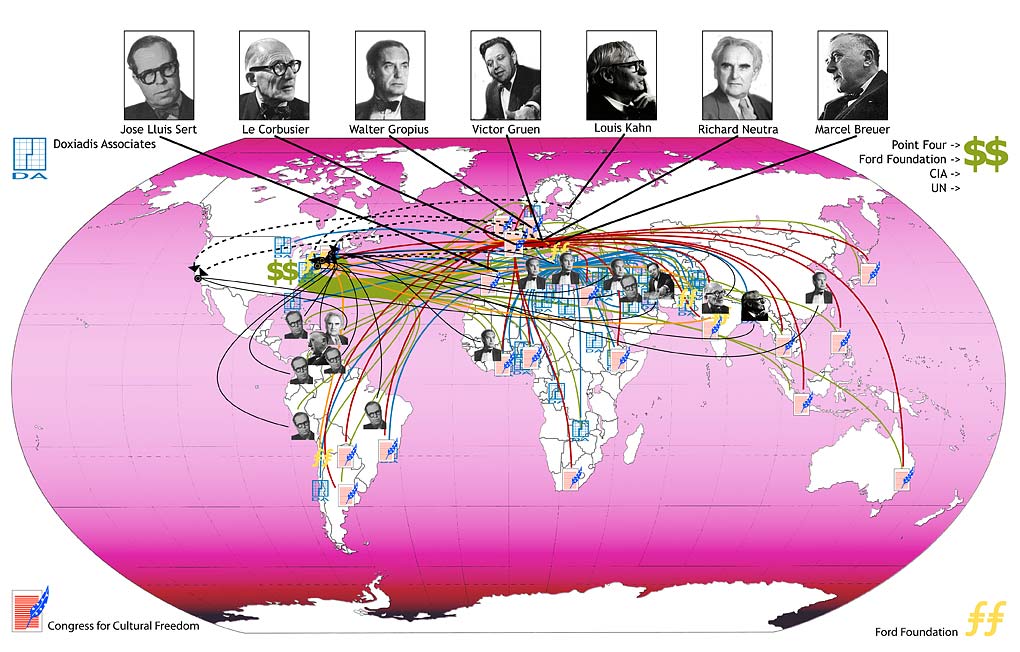

In the polarized atmosphere of the days there wasn’t a single American institution not cooperating in the ‘war on communism’; the State Department, the CIA, the United Nations, the Rockefeller, Ford and Carnegiefoundations, MIT, Rice and Harvard Universities, they all played a role in the cultural cold war. The unraveling of these intricate networks by interviewing people and going through dusty correspondence and faded microfilms has recently been my job as an amateur detective.

Introducing Doxiadis: Constantinos Doxiadis, nicknamed Dinos by his Ford Foundation-friends. He developed an extremely hermetic theoretical, design and engineering system called ‘Ekistics’, the science of human settlements. It was a rational and scientific alternative to the existing historical cities with their congestion of cars and people. Instead of those, Doxiaids proposed his gridiron cities, that would provide for a human scaled environment and at the same time facilitate unlimited growth, in people, money, cars etc. In that sense they were extremely well suited for development of any kind. Doxiadis was possibly the leading exponent of the explicit application of modernist planning and design models as vehicles for freedom, peace and progress according to a Western model.

Because of his political talents he was able to form an impressive international network with many USA and UN officials, which enabled him to design and built an oeuvre his colleagues could only envy. He probably constructed more urban substance than all his CIAM-colleagues together. In fact, after CIAM ended, he put up a conglomerate of training and research organizations as well as the Delos-conferences, which were clearly meant to take over where CIAM left off. He designed and built new cities all over the world, in Ghana, Zambia, Sudan, Lebanon, Pakistan, Iraq and the US.

How was it possible that this one office built so many largescale cities around the world while the most eminent urban planners failed? For instance: Sert was never able to realize any of his South American plans and Le Corbusier had to satisfy himself with only one, though heroic New Town, Chandigargh. Obviously Doxiadis got to build this empire not only because of his phenomenal charisma or the qualities of his work, but most of all because of the American support he received.

Introducing the Ford Foundation: the Ford Foundation is a private foundation erected in the thirties by Henry Ford himself, and was remodelled in 1950 to extend its activities outside the USA. Its main goals were formulated under the leadership of Paul Hoffman, formerly the coordinator of the Marshall plan in Europe. In that capacity he befriended Doxiadis, who allegedly used his last dime to show Hoffmann Greek hospitality by throwing a party in Athens with a semi-authentic group of Greek dancers. This proved to be a dime well spent. Hoffmann led the Ford Foundation on an ambitious quest for world peace, aiming to better the world by educating the ignorant, increasing their socalled “intellectual capacity and individual judgement” and easing them into democratic western civilisation. They tried to reach these noble goals mostly by investing in educational institutions –building schools also- and modernization programs in agriculture. Though urban planning was definitely not a main priority, Ford spent 5 million dollars on Doxiadis’ design and research, the largest sum they ever spent on one private party. Starting with a grant to Doxiadis’ design work for the city of Karachi in Pakistan in the middle of the fifties, Doxiadis and the Ford Foundation became a truly close couple.

By his connection to the Ford Foundation, Doxiadis was also immersed in the larger network connected to the Foundation. It had strong ties with official American foreign policy, which became visible in the exchange of board members between the Foundation, the American business world and policy makers in Washington. Also prestigious universities as Harvard and MIT were working in close relation to both Ford and the American foreign politics. They contributed mostly in terms of research and advice, and thereby assisted the Ford Foundation to effectively direct its grants. Usually the research at these centers, for instance the Harvard/MIT Joint Center for Urban Studies, was sponsored with millions of dollars by the Ford Foundation. Thus a constant feedback process was organized in which exchange of information, interests and funding took place between Harvard, the Ford Foundation and the government. There existed a complete consensus on the aims of the American elite to create peace and order in the world and it was seen as completely logical that private and governmental policies would mutually enhance and strenghten each other.

Still this doesn’t explain why particularly the work of Doxiadis –and not Sert, or Gropius- was judged to fit so well into this consensus. What qualities did the Ford Foundation detect in Doxiadis planning that made them recognize Ekistics as a useful instrument in their cultural cold war politics and what political goals did they attach to his urban planning?

Probably the answer lies in the extremely rational character of Ekistics and the way Doxiadis promoted his work as a science. He presented the outcome of his studies and designs in grids, charts, diagrams and schemes, almost like the work of a human computer, completely objectified, with no aesthetics or personal choices. In this pre-computer era there was no possible way to resemble computerwork any closer. Doxiadis was definitely no whimsical arty architect with crayons. He was a trustworthy engineer that could deliver. His Ekistics was a visionary, but nonetheless scientific system in which local data had to be entered and the design solution followed automatically. A touch of local landscape and architecture was inevitable and necessary, but not too much since this was contradictory with the universal pretentions of Ekistics.

This objective and rational approach completely fit into the philosophy of the Ford Foundation, which had formulated as its goal the education of non-western people into rational and sensible peoples, and thereby doing away with mistrust and latent violence. In fact, the Foundation exported with this goal one of the most fundamental values of the USA, as the eminent Cold War professor Od Arne Westad has analysed in his recent publication The Global Cold War. As the core values of the USA he singled out: liberty, anti-collectivism, a reluctance to accept centralized political power, and an absolute believe in science and technology as the progenitor of ‘rational action’. The American elite was convinced “that liberty was not for everyone, but for those who, through property and education, possessed the necessary independence to be citizens of a republic.” So: civilisation equals rationality. It was the task of the Americans to raise other peoples into a state of civilisation. When turning to urban planning it would have been hard to find an urban planning theory more rational than Doxiadis’ Ekistics.

But ofcourse the USA was facing a terrible dilemma, as Westad explains. On the one hand it was clear that: “American symbols and images –the free market, anti-Communism, fear of state power, faith in technology- had teleological functions: what is America today will be the world tomorrow.” On the other hand the question was what means and possibilities a democratic republic could ethically allow itself to influence other nations, a question which still is relevant. This is where the sometimes farfetched or ambiguous aidprograms come in handy, and the always intricate networks of cooperating government and NGO-institutions. It’s a way to exert control, not with the forceful instruments that an oldstyle empire would use, but in the noncommittal style of a free democratic republic.

Sometimes this went so far that control was exercised through covert operations. A clue on this came when two friends asked me separately to look into CIA-related issues. The one question was put very bluntly: was Doxiadis a spy for the CIA? The other question was about a sculpture of Naum Gabo in my hometown Rotterdam. It is an abstract metal sculpture, standing on a prominent spot in the busiest shopping street of the city, right in front of a fifties store designed by Marcel Breuer. My friend assured me that this statue was paid for by the CIA.

At first I thought it very unlikely that the CIA would even bother to get mixed into paying for artworks in the most pro-American city of the Netherlands. But it proved that the CIA was most certainy involved in manipulating the visual arts scene in Western Europe. In a thrilling 1999-publication the English writer Frances Saunders explains how the CIA perceived an inherent danger in the traditionally leftist arts world in Europe, and feared they might go over to the communist ideology. Their conviction was that to safeguard European culture, it was of the greatest necessity to win over the cultural and intellectual elite, since they would be the ones in charge of the future. To this end a ‘Kulturkampf’ started immediately after the war, right amidst the rubble of postwar Berlin, with both Soviet and allied sides competing in a frenzy of concerts, reading rooms, recitals, film showings and art exhibits.

Also architecture was involved: the wellknown publication Built in the USA, published in 1952 by the Museum of Modern Arts was among the translations published by the Psychological Warfare Division of the American Military Government, to showcase the developments in postwar architecture in the USA. It was received enthusiastically and turned out to be very influential in many western European countries and it was on the shelves of every modern architect in the Netherlands.

This cultural manipulation was institutionalized in 1950, when the CIA erected the Congress for Cultural Freedom, just a few years after Truman’s doctrine and the launching of the Marshall-aid plan. Together they formed a parallel set of political, economical and cultural measures to prevent Europe from slipping to ‘the other side’. The Congress’ mission was “to nudge the intelligentsia of western Europe away from its lingering fascination with Marxism towards a view more accomodating of ‘the American way’”. It was a ‘battle for men’s minds’, fought by the Congress with the help of an assorted group of radicals and artists, most of them disappointed in Stalin’s totalitarian USSR. They were musicians, writers, painters, actors and included wellknown names like George Orwell, Jean Paul Sartre, and Jackson Pollock. The Congress organised an impressive cultural offensive, publishing magazines in many different countries and languages, all over Europe and the third world, organising a flood of exhibitions of American painters (many in cooperation with MoMa), concerts and congresses.

Especially the position of Jackson Pollock and his fellow abstract-expressionists is fascinating: they were adopted by the Congress as the new cultural mascotte of the USA, much against the grain of prevailing taste in this country. But to the Congress the abstract expressionists embodied all the virtues needed in an artsmovement to project a new image of America to the old European countries; an image that would convincingly steer away from the stereotypical idea of Americans as ‘culturally barren, a nation of gum-chewing, Chevy-driving philistines” and would present the American culture as vital and superior to Soviet-culture.

To the American elite Pollock’s painting radiated the ideology of freedom, of free enterprise. It was non-figurative and politically silent, it was the very antithesis to socialist realism. Pollock was new, active, and energetic, while Socialist realist art was stiff, rigid and aping historical styles. Abstract expressionism was seen as a specifically American invention conquering the world, replacing the old centre of the arts, Paris, with New York. Also Pollock was exactly the right character to oppose the boyscout Soviet painters, who were obeyingly portraying the collective communist values. Pollock was a real, manly and rough American, and a drunk moreover, which was regarded as a proper asset for an artistic figurehead.

Again, the Ford Foundation was very close to the Congress for Cultural Freedom. The number of personal connections, of personel changing jobs from the one to the other organisation are so manifold, that it could justly be called a sisterorgansation of the Foundation. Ford over the years granted almost 10 million dollars to the Congress and eventually even became the main financer.

Now, bringing this back to Doxiadis and urban planning: though the Congress for Cultural Freedom didn’t have architecture or urban issues as a priority, Doxiadis was among the very few architects involved in the Congress’ activities. In their important 1955 congress in Milan he was among the lecturers, where he spoke about the “Economic progress in underdeveloped countries and the rivalry of democratic and communist methods”. In 1960 he was a member of the select group that attended the congress on the New Arab Metropolis, together with Hassan Fathy, then a member of his office. These CIA-initiated congresses were paid for by Ford. Of course Doxiadis’ involvement with the congress doesn’t prove he was a CIA-agent, but, it does allude to a hypothesis on the meaning of his work to the CIA and the Ford Foundation, that would finally explain their strong preference for Doxiadis’ work.

I’m using the CIA and the Ford Foundation almost as interchangable institutions, because they operated from exact the same mindset. With the risk of sounding like paranoically suggesting a complottheory I would say that the Congress for Cultural Freedom, the Ford Foundation, US government, Ivy League Universities, but also other private funds like the Rockefeller and Carnegie foundations all worked together to accomplish the same goal of fighting ‘the war on communism’ to use a modern paraphrase. They would divide tasks among each other: whenever a certain activity wouldn’t fit into the program of the Ford Foundation, they would ring up the director of the Congress and he would finance or organize it. The CIA would step by the Ford Foundation weekly, discuss their own plans and delegate them to Foundation-officials. This period was by most people involved described as a very passionate time, an exiting amalgamate of covert operations, boudoirpolitics, intuitive actions, lots of travelling, lots of pretense, lots of money and especially: no doubt that all this was completely justified, useful, ethical and just. A beautiful, high-minded episode, and everyone loved to be part of it. They felt they were “the most priviliged of men, participants in a drama such as rarely occurs even in the long life of a great nation”. You just can’t help feeling envious.

To these men, Doxiadis was as much a mascotte in the field of urban planning as Jackson Pollock was in the artsscene. Whereas Pollock was the antidote to social realist painting, the work of Doxiadis posed the complete opposite to social realist urban planning and architecture. The USSR cities after the war, up to the arrival of Chroestjov at the end of the fifties, strongly showed the mark of Stalinist planning. Up to a thousand New Towns were built all over the massive country, using a wellknown and historical repertoire both in urban planning as in architecture. The vista, the axe, the square, the closed housingblock, the monumental, palazzo-inspired architecture; they all evoked an urban image aspiring to be recognizable and familiar to the common people.

While Pollock proposed a completely new direction in painting, and freed himself from historical precedents and iconography, Doxiadis’ Ekistics posed a completely new system in urban planning, freeing it from formal design, and replacing it by organizing the urban area in ever enlarging grids and systems, eliminating monumental composition and replacing it with schemes for unlimited growth and change. His Dynapolis and eventually Ecumenopolis, the world-encompassing city, exploded all known scales in urban planning. The neighbourhood unit, known from the English New Towns, was stretched and repeated and put in an endless spaced-out grid, until every reference to existing urban settings had vanished. Ideologically important was the fact that the state-imposed collectivism of social-realist planning was replaced by the emphasis on bottom-up communities. Moreover, the ideas of change and growth without boundaries and technology solving every possible problem, from demographic growth to energy shortage to pollution to economic backwardness to ethnic and social unrest, all this made Doxiadis’ vision the perfect vehicle of the USA-development ideology.

The Ford Foundation described its urban planning projects (in India, Yugoslavia, Chile, Pakistan) as ‘white bread’, the innocent, soft bread, with no particular taste, which everybody likes. They could ease the way for a different lifestyle, western, efficient, peaceful, and help the third world countries to become rational civilizations and grow towards a welldeserved autonomy. In this sense it is not an exaggeration to call Doxiadis’ work part of the cultural and economic imperialism of the west in the developing countries.

The Middle East, located right below the soft underbelly of the USSR and therefore a main stage for Cold War activities, was virtually a playground for American architects in the fifties. They followed in the wake of American and international aidprograms like the Point Four program and the United Nations Development Decade. They were hired by the puppet regimes installed by ‘the coalition’ of the British and Americans.

In Iran, ruled by Shah Reza Pahlavi, Victor Gruen designed a masterplan for the capital Tehran and numerous American offices flooded the country to work on New Towns. The Iraqi regime of King Faisal hired Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, Gio Ponti, Alvar Aalto and Frank Lloyd Wright. Again, there’s a Havard-connection here: this select group of foreign architects was invited by a married couple of Iraqi Harvard GSD graduates, former students of Walter Gropius, of whom the husband’s father was the prime minister.

The American Aidprograms, focused on Lebanon, Iraq or Iran, often underestimated the complexities of the country. Without speaking the language, with insufficient knowledge about the local social customs these well-intentioned but amateuristic efforts often missed target. In the case of Iran a group of five American planners took the adventure. When they arrived in 1957 they found out, much to their disgust and disappointment, that the cities in need weren’t exactly metropolitan, didn’t have any comfortable means of transportation, no services, no shopping, no education etc. They had the greatest possible troubles to interact with the local officials, there were permanent issues of hierarchy and frustrations about lack of cooperation and lack of almost everything else. The most enthusiastic planner, working in the Kurdish city Sanandaj in western Iran, finally succeeded in setting up a small planning department along western lines, complete with an office and drawing boards. But after he left for a two week honeymoon he came back to find the office wrecked by a storm and his newly trained planners had disappeared, they never came back. In short, there was an unbridgeable gap between the western, rational planning methods the Americans longed to impose and the existing local traditions and habits.

Compared to these rather naïve efforts, the results of Doxiadis’ office were of the utmost efficiency and effectivity. Especially in Iraq, where he was hired to design a modern national housing program including the capital Baghdad, Doxiadis showed what he was capable of doing: practically on his own he brought in a complete ministry of housing, planning, architecture, and architecture training. Gropius’ office was struggling to get the designs for the Baghdad University built, and only succeeded in realizing one tower twenty years later, and Frank Lloyd Wright saw his grandiose plans for the Baghdad Opera thrown out the window when the revolutionary regime took over from King Faisal in 1958. But Doxiadis didn’t have any problems: his multidisciplinary team made surveys, wrote reports, designed tens of thousands of houses and was able to build them as well. Still, the official architectural history has shown a disproportionate interest in those highprofile architects’ failed designs, neglecting the far more influential work of Doxiadis.

Unknowingly everybody has seen the results of his work on CNN. By the end of the fifties Doxiadis built areas in Iraqi towns which bear the by now wellknown names of Mosul, Basrah and Kirkuk. The largest number of houses was realized in Baghdad, on the eastbank of the Tigris; the endless repitition of square neighbourhood units are easily recognizable on any satellite image. This is the area called Sadr City. By now it is mostly known as a nightmarish ghetto and the gruesome décor for warfootage. The area has been a hotbed of resistance against the Americans, inhabited by two million mostly Shia Iraqi’s. It consists of endless areas of low-rise but high-density development, with narrow alleys and culs-de-sac, grey concrete slums and small rowhouses. Sadr City even has the dubious honour of being featured in a multi-player computer wargame on Internet, called Kuma War: Mission 16, Battle in Sadr City.

Sadr City was designed by Doxiadis as part of his 1958 masterplan for Baghdad. Doxiadis’ design follows the Ekistics rules and is quite identical to his other contemporary urban designs, be it Islamabad, Tema or Khartoum. Doxiadis encased the historical centre of Baghdad in a orthogonal grid extending on both sides of the Tigris/Euphrates, composed of 40 sectors of some 2 square kilometers each, separated from each other by wide thoroughfares. Each sector was subdivided in a number of ‘communities’, with smaller neighbourhood centres and housing areas served by a network of cul-de-sacs. Each community center consisted of a modernist composition of market buildings, public services and a mosque. The rowhousing was organized in such a way that the smallest communities each had a ‘gossip square’, an intimate open meeting space inspired by existing local Iraqi customs. Though these small oases could be interpreted as contextual elements, as a whole the extension of Baghdad was a generic, universal system Doxiadis thought appropriate for almost any developing city with a hot climate. Also the architecture was generic with some local touches; a restrained modernist architecture with decorated pannels in a pattern slightly reminiscent of Arab motives, built with local materials, but not in any outspoken vernacular style. Local influences had a very limited, technical meaning to Doxiadis: it meant using local techniques and building methods, but did not involve using local identity or cultural traditions.

The most appealing feature of Doxiadis’ plans for his American patrons and the Ford Foundation in particular was the emphasis on community building. Something that was to be avoided at all costs was that the cities should have an alienating effect on the millions who were often the first in their families to lead a modern urban lifestyle. After all, alienation would lead the population to turn in frustration to communism or to revert to archaic traditions of superstition and violence. We could therefore regard the cities designed by Doxiadis with their smallcale urban design of gossip squares, little streets and community centres, as precisely tuned ‘emancipation machines’. This emanicipation was part of the modernization package, which included democratic institution building and economic reforms to create a free market.

In retrospect, one thing is for certain: the urban planning projects in Iraq, Iran or Pakistan didn’t have the effect the Americans hoped for, of creating a stable democratic mentality, that would secure the way for western foreign policy. The inherent suggestion that a plan with an open lay-out, symbolic of an open society, would also help to accomplish becoming one, hasn’t been successful. It goes to show though, how high the expectations once were of what urban planning could accomplish.

Of course it is tempting to compare the present situation in Iraq with the Cold War episode. Again there is the attempt of the USA to impose its own ideas on Iraq, this time, as Naomi Klein has analysed, the neoconservative idea of freemarket economy. Even officials who were part of the American policy making in the fifties, like the eminent professor of history William Polk, now issue warnings not to make the same mistake twice: of imposing structures, ideas, organizations and plans that are not wanted and not indigenous to the local culture. As Polk has simply and truly stated: not only the USA, but all countries want to determine their own destiny. We could add to it: all countries also want to determine their own architecture. Architecture and urban planning are not ‘white bread’ as the Ford Foundation stated, they are not technical works with no inherent meaning or taste; to the contrary, by their organization they project a strong ideal image of a specific kind of society. But however you judge Doxiadis’ cities and however critical you might be, there was at least an ideal behind it, while at this moment it would be very difficult to find any positive images of the future Iraq.

It may seem extremely embarrassing to compare Baghdad with the European New Towns, of which the problems and circumstances are of a totally different nature. There is one obvious parallel though: also in Europe there was a cultural and policial mission hidden somewhere in the technocratic project of the industrialized and standardized city: the idea that these New Towns could function as instruments of emancipation and modernization. In Europe, like in Baghdad, the open design had an extra meaning: to shape the minds of the inhabitants, to open their minds to the open democratic society. And also here, these ideals haven’t turned out as planned. While that may be true, one thing is clear: the presentday situation in which everybody in the architects and planning community agrees that the postwar cities are a complete failure has only lead to a set of non-productive strategies. In Academia there is a tendency to study postwar modernist planning and to analyze the original concepts to the bone, to the point of obsession even. Minutes of the few Ciam meetings have caused a library full of analytical discourse and the unrealized designs of Sert, Le Corbusier or Kahn are still being unraveled like they were the Dead Sea rolls. But studies like these tend to banish modernist architecture and planning to a far away and long ago age, almost forgetting that there are real cities out there, with real people in it, that you can go to and walk around in and that have problems to be solved.

On the other hand practising architects and planners have either completely ignored the existence of the not so sexy and glamorous New Towns or they have clung to the tabula rasa approach of erasing them and starting anew. This can hardly be the proper solution: the postwar urban substance is simply too big, there’s too many people living there, and starting all over again is creating the same problem all over again. The problem of the deteriorating postwar areas cries out for creative urban planning, research and design, which reuses the existing material, both in its fysical and social sense.

And it doesn’t really matter if we talk about Baghdad or Hoogvliet: both are part of the same 20th century heritage we have to deal with and even the bottom line of the moral questions is about the same. WiMBY! has made the statement in Hoogvliet that the values inherent in the modern planning - democracy, the collective, emancipation - still have relevance, though their architectural forms may change. Other cities come up with different positions. Whenever a city in the Netherlands or Denmark is being restructured it makes a lot of sense to study the social organizations that have uplifted the neighbourhood of 23 Enero in Caracas, Venezuela, or to Indian cities where inhabitants have appropriated their modernist housingblocks by decorating them in a horror vacui of personalized symbols and signs. On the other hand projects developed in the restructuring of European cities might well be an instrument to be used in the rebuilding of Islamabad or Baghdad. It is necessary that the legacy of modernist urban planning is being reconsidered, that all these visions on its future are made known and exchangeable, and that the New Towns are being treated as what they are: real cities not be erased, but waiting for a serious design strategy that will add another layer of urban material, and turn them into normal, growing, developing, aging cities.